Mobile banking service

According to Barnes and Corbitt (2003), the first m-banking application was deployed for users in Europe to make bill payments and check their account balance, as early as 1990. Barnes and Corbitt (2003) determined “m-banking as a channel whereby the customer interacts with a bank via a mobile device” (p.3). Tiwari et al. (2006) claimed that m-banking is the cornerstone of mobile commerce and is seen as the availability of banking- and financial-related services via smartphones. The scholars stated that “mobile banking refers to provision and availment of bank-related financial services with the help of mobile telecommunication devices” (Tiwari et al., 2006). The study by Ngai and Gunasekaran (2007) argued that mobile banking and payments were the most popular mobile commerce applications that support financial activities. As explained by Yuan et al. (2016), “m-banking means that users adopt mobile terminals such as cell phones to access payment services including account inquiry, transference, and bill payment” (p.20). Shaikh and Karjaluoto (2015) posited that m-banking was a type of mobile commerce that was an essential business model based on the mobile application service system. Researchers use interchangeable terms to refer to mobile banking, including mobile banking, mobile payments, mobile transfers, mobile finance, and smartphone banking (Ashique Ali and Subramanian, 2022; Shaikh and Karjaluoto, 2015; Susanto et al., 2016). These terminologies are targeted services of various studies; while they are slightly different in features (e.g., money transaction), they combine to form the family of m-banking services. One of the most popular m-banking services is mobile payment. Mobile payment is a set of financial services performed by installing an application on a smartphone, for customers to pay sellers (e.g., bank, corporate, individual) for products, services, and bills.

Continuance intention and expectation-confirmation model

Continuance intention

The term “IS continuation” refers to the user’s decision to continue using the information system (IS) after initial acceptance (Bhattacherjee and Barfar, 2011). Bhattacherjee (2001) defined IS continuance intention as a user’s intention to continue to use an IS, and continuance could happen just after acceptance (first usage) to distinguish between the two concepts of behavioral acceptance and continuance (Bhattacherjee and Lin, 2015). Nabavi et al. (2016) described it as the user’s post-adoption behavioral patterns, which included both continuation intention (CI) and continuance usage (CU).

The majority of the IS literature over the past two decades has focused on user adoption and initial usage of IS (Nabavi et al., 2016; Susanto et al., 2016). In contrast to the number of studies on initial adoption, continuation intention has attracted comparatively little attention (Hong et al., 2017). There is a shift in focus from user adoption to the continued use of individual behavior at the post-adoption stage. (Bhattacherjee and Lin, 2015; Tam et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021). As a result, research on IT continuance has increased rapidly in recent years and spread to various contexts (Franque et al., 2021), such as continuance intention in mobile information systems (e.g., mobile payment), social network systems (e.g., social networking) (Sullivan and Koh, 2019) and electronic business information systems (e.g., mobile commerce) (Gao et al., 2015).

Yan et al. (2021) posited that the three theories that researchers use frequently to explain CI are the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis et al., 1989), expectation-confirmation theory (ECT) (Oliver, 1980), and IS continuance model or expectation-confirmation model (ECM) (Bhattacherjee, 2001). TAM was initially used to predict the possibility of new IS, assuming the influence of perceived ease of use and the perception of usefulness on attitude toward technology acceptance (Davis et al., 1989). An expansion of the ECT and TAM is the ECM that has posited that after initial adoption, a user’s satisfaction with the technology and assessment of the system’s value may develop, leading him/her to use the technology (Bhattacherjee and Lin, 2015).

Expectation-confirmation model

Rooted on the ECT, Bhattacherjee (2001) has suggested the expectation-confirmation model to predict user IS continuance intention. While ECT has been extensively utilized in consumer behavior to examine user satisfaction, repurchase behavior, and service marketing as a whole (Yuan et al., 2016), ECM is the foundation of a post-acceptance model used in IS literature to investigate the impacts of user perceptions and expectation in technology continuance (Bhattacherjee, 2001). The ECM has posited that confirmation from a previous use of technology substantially influences satisfaction and perceived usefulness (PU), which were strong determinants of CI. Confirmation refers to the agreement between the IT product’s actual and expected performance. ECM has discussed the distinction between the initial adoption and continuance behavior of IT products/services (Sreelakshmi and Prathap, 2020). According to ECM, consumers may have expectations before using items. After using these items, they assess the performance to gauge their satisfaction and continuance intention. Scholars have argued that other important factors have a direct or indirect impact on the continuation intention (Nguyen and Ha, 2022).

The ECM has been used in research to analyze users’ continuous use of IS contexts such as ride-hailing (Malik and Rao, 2019); food delivery services (Ramos, 2022), and mobile payment (Purohit et al., 2022; Sasongko et al., 2022). Thanks to ECM’s capability to examine continuation intention in the context of mobile apps and financial services, the model is used in this study to predict users’ continuance intention in the m-banking context.

Confirmation and PU are the factors that determine whether customers are satisfied with the IT. In many contexts, such as those involving the internet, information systems, and m-commerce, PU is a significant predictor of behavioral intention (Nabavi et al., 2016). Furthermore, confirmation may be used to express the perceived usefulness of IS, particularly when the users’ first perception of usefulness is not definite since they are unsure of what to expect from utilizing the IS.

Prior studies identify various antecedents of CI, which are divided into four basic categories: technological, psychological, social, and behavioral factors (Yan et al., 2021). Poromatikul et al. (2020) studied the post-adoption of m-banking and found that continued usage is strengthened by satisfaction, perceived usefulness, trust, and confirmation.

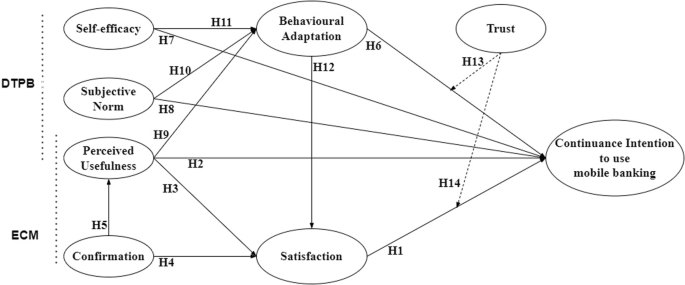

As this study is grounded in ECM, our research model has inherited the original ECM’s five factors (i.e., confirmation, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and continuance intention) and its generic hypotheses. Based on the ECM and the aforementioned prior published studies (Ha et al., 2022; Tam et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2016), this research proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Users’ satisfaction is positively associated with continuance intention to use m-banking.

H2: Perceived usefulness is positively associated with continuance intention to use m-banking.

H3: Perceived usefulness is positively associated with users’ satisfaction.

H4: Confirmation is positively associated with users’ satisfaction.

H5: Confirmation is positively associated with the perceived usefulness of m-banking.

Decomposed theory of planned behavior

The work by Taylor and Todd (1995) applies the TPB to technological innovations by decomposing its monolithic or unidimensional belief structures into a set of multidimensional constructs that explain user behaviors in various IT-enabled contexts (p.140). While TPB (Ajzen, 1991) includes unidimensional belief structures, including attitudes, subjective norm (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC) (e.g., self-efficacy), decomposed TPB disintegrates these structures into multidimensional contextual variables. According to DTPB, (1) behavioral belief or TPB’s attitude is fragmented into three factors compatibility, complexity, and relative advantage; (2) normative belief is a subjective norm; (3) control beliefs are divided into the efficacy and facilitating conditions. Researchers have largely employed DTPB to predict user pre-adoptive (i.e., adoption) and post-adoptive usage of IT-enabled services in numerous settings. Rodríguez Del Bosque and Herrero Crespo (2011) have investigated users’ acceptance of e-commerce. While Lau and Kwok (2007) investigated how e-government strategies impact small and medium enterprises (SMEs), Ajjan et al. (2014) inspected employees’ continued usage of a company’s instant messaging applications. Regarding the app-based business context, researchers have studied the associations of SN, PBC with CI on m-commerce acceptance (Khoi et al., 2018), the impacts of PU and SN on user satisfaction and continued usage intention towards ride-hailing applications (Joia and Altieri, 2018). In mobile banking, a few researchers have applied DTPB (Souiden et al., 2021), for example, Zhou (2014) examined continuance usage. Thus, the DTPB’s application can enlighten the behavioral usage and intention in the mobile banking setting. Three DTPB’s belief structures are prospective determinants of customer behavioral adaptation and continuance usage (Taylor and Todd, 1995).

Subjective norm

TPB and DTPB view subjective norm (SN) as a key social determinant encouraging user intention to specific actions (Bhattacherjee and Lin, 2015; Mouakket, 2015). SN is denoted as the perceived external pressures (e.g., from important people) on whether to conduct a specific action in a certain situation (Lee and Kim, 2021). In our study, the subjective norm is regarded as recommendations, guidance, or opinions from key persons (i.e., colleagues, friends, or family members) for users to use mobile banking (Mohammadi, 2015). The influence of SN on user behavioral intention has been recognized by previous studies, including Fu and Juan (2017) in transportation service, Liébana-Cabanillas et al. (2015) in m-payment, Marinkovic and Kalinic (2017) in e-shopping, Zhao and Bacao (2020) in food-delivery services, and (Hamilton et al., 2021) for e-health services. The more the customers accept suggestions, the more likely it is that they will decide to use mobile applications. Recently, the importance of the associations between SN and satisfaction, behavioral intention, and actual use of m-application services has been reported in fintech and mobile banking studies (Daragmeh et al., 2021). Hence, the study suggests two following hypotheses:

H8: Subjective norm is positively associated with continuance intention to use m-banking.

H10: Subjective norm is positively associated with behavioral adaptation to m-banking.

Self-efficacy

According to the DTPB, facilitating conditions and self-efficacy (SE) that are distinct from a user control belief, influence both behavioral intention and actual usage behavior. Bandura (2010) explained SE as users’ beliefs in their abilities to act effectively and stated that self-efficacy judges “how people feel, think and behave” (p. 1). A prior study by Gupta et al. (2020) examined user SE and its significant impact on behavioral intention in Internet banking and payment. While Thakur (2018) denoted that SE is linked to continuance intention in m-commerce, Kang and Lee (2015) posited that SE is a determinant of CI towards online services. In e-learning, Rekha et al. (2023) argued that SE impacts users’ behavioral usage activities. For the ride-hailing service, while Malik and Rao (2019) examined the linkage between SE and continuance intention, Nguyen and Ha (2022) advanced to study further how SE influences user behavioral adaptation and continuance intention. Thus, we hypothesize the following hypotheses:

H7: Self-efficacy is positively associated with continuance intention to use m-banking.

H11: Self-efficacy is positively associated with behavioral adaptation to m-banking.

IT adaptation and adaptive structuration theory for individuals

There are various definitions of IT adaptation (Nguyen and Ha, 2022), such as reinvention (Rogers, 1983), mutual adaptation (Leonard-Barton, 1988), appropriation (DeSanctis and Poole, 1994), post-adoption (Jasperson et al., 2005), and so on. Researchers claim that technological adaptation refers to modifications and changes made once a new technology is installed in a specific organizational context (Orlikowski, 2000). Leonard-Barton (1988) stated that adaptation is mutual adaptation because of that technology features and users’ behaviors need to adapt to each other simultaneously and efficiently. Rogers (1983) argued that users could continue to use IT when the spread of an IT reaches the confirmation phase as it is adopted. IT implementation literature (Jasperson et al., 2005) has classified the process into six phases (i.e., initiation, adoption, adaptation, acceptance, usage, and incorporation). Amongst these phases, adaptation is considered to be one in which users perform actions on the IT to assimilate it appropriately into their workplace.

According to Ha et al. (2022), there is a prevailing framework for exploring IT adaptation that involves a pair of theories including adaptive structuration theory (AST) (DeSanctis and Poole, 1994) and adaptive structuration theory for individual (ATSI) (Schmitz et al., 2016). The difference between the two theories is that while the AST is generally applied to study organizational and group adaptation, the ASTI is applied at the individual level. In contrast, the commonality is that both theories defined the adaptation process as a consequence of a “structure episode”, the mutual interaction between IT and the user’s task in the workplace. The adaptation process has three characteristic input blocks, including technological, task, and personal characteristics, that create the output of better decision outcomes (DeSanctis and Poole, 1994; Schmitz et al., 2016). Accordingly, when implementing IT into group or individual activities, users try, modify, and adapt the IT to achieve better outputs or make decisions. Additionally, the task-technology fit (Goodhue and Thompson, 1995) considered IT utilization as an integrated concept having three adaptive elements (i.e., technology, task, and individual actions with both). Inspired by TTF, Barki et al. (2007) formed the Information System Use-Related Activity Model (ISURA) that defined individual adaptation as a combination of three factors including interaction, task-technology adaptation, and self-adaptation. Furthermore, according to Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2005), user adaptation is coping behaviors that are employees’ efforts relevant to technology, work, and personal factors. Thus, IT adaptation is explained as user behaviors that show how people use and change technology, how decisions are made, how well they perform, and whether they continue working with the IT (Barki et al., 2007; Beaudry and Pinsonneault, 2005; Nguyen and Ha, 2022). Considering prior seminal research, this article has defined user adaptations as activities performed by users that adjust the features of m-banking applications and practices of doing banking to meet their preferences, necessities, and circumstances. Therefore, behavioral adaptation for a mobile banking service can increase customer satisfaction and encourage customers to keep using it in the future.

Even though studies have identified IT adaptation as a determinant in post-adoptive behavior or continuation, research on this topic has not yet been completed. (Bhattacherjee and Barfar, 2011; Nguyen and Ha, 2021). Very few researches confirm the impact of user adaptation on CI and investigate it in the context of mobile banking. To address this gap, this study intends to investigate the correlations of behavioral adaptation with user satisfaction and continuance by hypothesizing the following:

H6: Behavioural adaptation is positively associated with continuance intention to use m-banking.

H12: Behavioural adaptation is positively associated with user satisfaction.

In addition, the construct of perceived compatibility towards a specific behavior is considered comparable to expected performance or PU (Taylor and Todd, 1995; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Thus, it is the user’s perceived usefulness of the m-banking app characteristics and its service advantages over traditional financial payment methods that combine to encourage users to utilize the m-banking service (Susanto et al., 2016). Based on these theories and the aforementioned argument, we propose the following:

H9: Perceived usefulness is positively associated with behavioral adaptation to m-banking.

Trust

Trust is studied in many different contexts and has various definitions, reflecting the meaningful nature of trust (Soleimani, 2022). One of the most acceptable definitions in the marketing and information technology literature of trust is proposed by Mayer et al. (1995), who claim that trust is understood as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (Mayer et al., 1995). In the e-commerce environment, researchers argued that trust helps users to overcome their perception of risk and unwillingness, and users are likely to conduct the following actions: accepting recommendations from e-commerce vendors, sharing information online, and, most importantly, purchasing from e-commerce applications (McKnight et al., 2002). Trust is seen as consisting of three belief components, including ability, integrity, and benevolence.

While ability means that m-commerce providers have the knowledge and skills to accomplish their duties, integrity means that they will maintain their commitments and not betray the consumers, and benevolence means that online commerce businesses prioritize and care for their consumers’ benefits, not just their own. In mobile payment, scholars have claimed that trust is the faith that encourages online buyers to become willingly susceptible to the m-payment providers after realizing the characteristics of the payment from which they are dealing (Al-Adwan et al., 2020). Another point is that in m-commerce, while Wei et al. (2009) denoted that trust is a belief in the safety of using m-commerce, Sasongko et al. (2022) referred to trust as the willingness of users to take risks caused by the transactions of another party (e.g., a bank), believing in the expectation that the bank will take beneficial action in favor of the bank users. Researchers also posited trust as an essential direct influencer of continuance intention in the online shopping context and mobile payment settings (Poromatikul et al., 2020).

Drawing on prior studies, in our study, trust is the belief that enables users to engage in m-banking service voluntarily, while considering its susceptible mutual features. Trust likely reduces the user’s perception of risk and reluctance and encourages user initial usage (i.e., pre-adoption), enables users to make use of m-banking services and leads to continuance usage (Gao et al., 2015; Nguyen and Ha, 2021). While trust is inspected as a contingent factor in limited contexts such as human resources (Zhou et al., 2022), online hospitality (Han et al., 2022), and e-government (Lee and Kim, 2022), very few explored its moderating role in the financial sector such as mobile banking (Ashique Ali and Subramanian, 2022). For e-wallet services, Senali et al. (2022) have investigated the role of trust as a moderator in the interactions between users’ perceptions of the service (e.g. perceived usefulness) on intentions to use. Chong et al. (2023) have investigated the moderating effect of trust on CI in the e-commerce context in Malaysia. As such, based on previous studies, we propose the following:

H13: Trust moderates the relationships between adaptation and users’ continuance intention in using m-banking.

H14: Trust moderates the relationships between satisfaction and users’ continuance intention in using m-banking.

Thus, based on the above theoretical references, the research model including theoretical hypotheses is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Research model.

Source: authors based on the theoretical references.