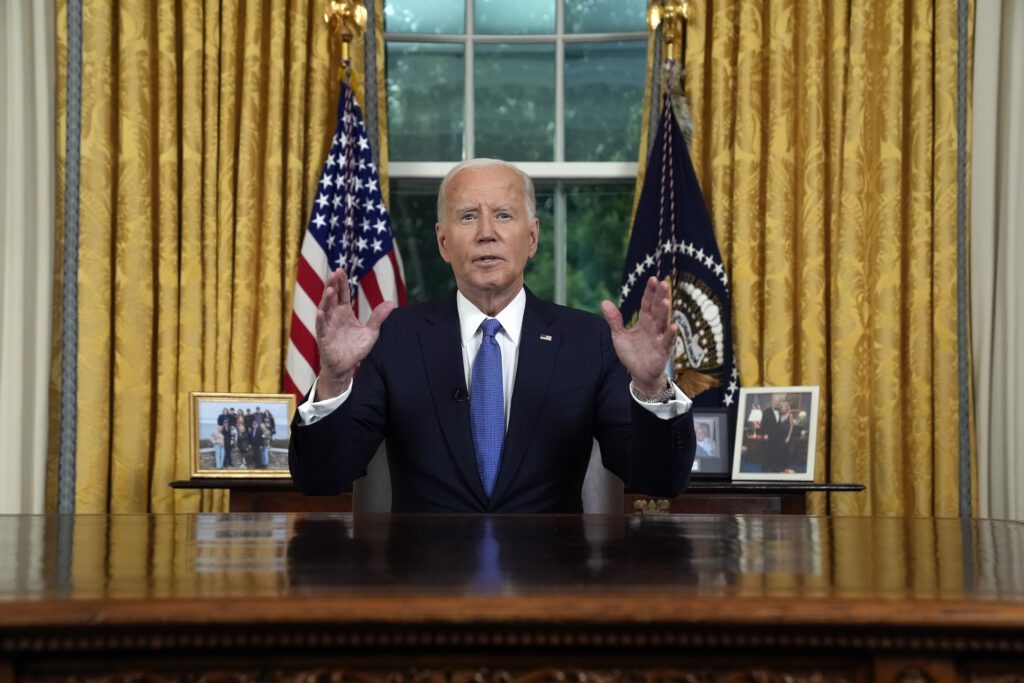

Cybersecurity policy under the Biden administration marks a dramatic shift: Over the past four years, the strategy has been articulated to shift the burden of protection from consumers to those most able to do so, particularly the private sector, which produces the technology and owns our most critical infrastructure.

This is a sweeping overhaul currently underway across 16 critical infrastructure sectors where protection is a federal priority, from the White House to the Federal Housing Administration. The effort has resulted in regulations that establish minimum security standards in new areas, supported by a range of voluntary initiatives.

The changes have faced criticism for going too far and not going far enough. Some aspects are likely to remain regardless of the outcome of the next election. If Vice President Kamala Harris is elected, the current course is expected to continue. If former President Donald Trump wins, the Republican platform vows to “raise security standards for critical systems and networks.”

But the road ahead is otherwise uncertain, with the agency’s regulatory powers unclear in the wake of a landmark Supreme Court decision. Already the courts have proven a roadblock in one key area: the fragile water sector.

Based on interviews largely conducted before Biden announced he would not run for a second term, here’s how the Biden administration’s top cybersecurity official and outside experts assess this momentous change.

How it happened

This shift began, at least in part, before President Joe Biden took office: Anne Neuberger, the deputy national security adviser for cyber and emerging technologies, worked at the National Security Agency before Biden was elected and didn’t like the direction cyber defense was taking.

“I took this job believing for a long time that voluntary approaches to cybersecurity were not going far enough,” she said, looking back to the time before the Biden administration. “We’re still seeing the same basic cyber attacks, and we were doing the same things back then, when the number of attacks had just increased exponentially. So I took this job feeling like we had to do a better job, and frankly, just about every country in the world was already doing that and had minimum requirements in place.”

The Biden administration quickly drafted executive orders to leverage the federal government’s vast buying power to encourage industry improvements among contractors and, indirectly, across the private sector. But by the summer of 2021, momentum for increased industry regulation was building in the wake of cyberattacks on Colonial Pipeline that sparked a fuel panic and on meatpacking company JBS that threatened meat supplies.

“It’s definitely had a big impact,” Neuberger said. The Colonial Pipeline attack caught the attention of the president, and Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas issued a security directive to major U.S. pipeline companies through the Transportation Security Administration.

“That was a big change in the US,” Neuberger says. “After the Colonial Pipeline incident, people said, ‘How is this possible? How can a criminal group shut down a major regional pipeline?’ And the answer was, ‘If we have to shut down a pipeline, we’re a big company that affects millions of Americans, and we don’t have cybersecurity standards.’ So we said, ‘Well, let’s actually look at what emergency authorities exist.'”

accounting

The TSA pipeline rule spawned other rules from the TSA for air and rail carriers, and other agencies followed suit, ranging from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s disclosure rules for all publicly traded companies to the Federal Communications Commission’s less visible but crucial steps to protect the internet’s backbone.

In 2022, Congress passed, and President Biden signed, a bill requiring critical infrastructure companies to report large-scale cyberattacks to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and in early 2023, a national security strategy led by the Office of the National Cyber Director outlined the goals.

“Individuals, small businesses, state and local governments, and infrastructure operators have limited resources and competing priorities, but the choices these actors make can have significant impacts on the nation’s cybersecurity,” the strategy states. “A single individual’s momentary lapse in judgment, use of an outdated password, or accidentally clicking a suspicious link should not affect national security. … Rather, we must do more to call on the most capable and best positioned actors, both in the public and private sectors, to make our digital ecosystem secure and resilient.”

These standards are accompanied by policies with similar goals, including additional executive orders covering other technologies and sectors, voluntary programs to encourage secure software design, and cybersecurity labeling initiatives similar to the Energy Star program.

How is it happening?

CISA Director Jen Easterly said that in leading the “Secure by Design” initiative, CISA recognized and pushed forward with a long-term trend.

“From the birth of the internet to the mass adoption of software, the past 40 years have seen a technological revolution that has pushed safety and security to the back burner, and led technology and software manufacturers to prioritize speed to market and functionality over security,” she said. “The future we envision is one in which harmful cyber intrusions like ransomware attacks never happen.”

About 170 organizations have signed the pledge since CISA launched the initiative in 2023, which Easterly said is one sign that the initiative has “captured the zeitgeist.” But she noted that this change in thinking may take time to take hold, just as it took decades for Ralph Nader’s push for seat belts and airbags in cars in the 1960s to become widely accepted.

“This is a big cultural change,” Easterly said, “and I think it will take longer to really have an impact,” adding that it will also require more data that CISA will eventually collect under the Cyber Reporting Act, known as CIRCIA.

Perhaps a more distant goal touches on the same theme: shifting legal liability for cyberattacks onto software makers. “Software makers can use their market position to contractually abdicate responsibility entirely,” the National Cybersecurity Strategy states. It’s an area that National Cyber Director Harry Coker has identified as one of the toughest problems his office is working on, including convening academics earlier this year to discuss the concept as a “starting point,” he said.

Corker is not satisfied with the progress being made in shifting the burden: “If you look at the National Cybersecurity Strategy and what it’s asking organizations, individuals and entities to do, and the policies that are in place, if we all did all of that, we would see a significant reduction in intrusions, and that’s not happening,” he said.

Neuberger also wants to see more done. “What we’re doing is something we should have been doing a long time ago. I wish we could go further,” she says. “We’re trying to measure it so that we know the threat is high. We’re low. We’ll eventually move up to medium. We need to get to a state where, at the very least, our defenses are able to spot attacks quickly and push them out. We’re not there yet. Right now we’re just doing the bare minimum to make it costly and difficult for attackers to attack us.”

Private Sector Response

Not everyone has embraced the government’s approach, especially when it comes to minimum standards. Some in industry have been critical, but the private sector has softened its opposition in certain areas after the agency made changes in response to complaints. But a lawsuit by Republican state attorneys general has derailed the Environmental Protection Agency’s plans for a water security rule, and some Republican lawmakers have challenged certain of the agency’s standards.

“I think the administration and its agencies’ cyber regulations have done more harm than good,” said Rep. Andrew Garbarino of New York, chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee’s cybersecurity subcommittee. The set of rules can put companies in a position where they have to report incidents to one agency within 12 hours, another within 48 hours and yet another within 72 hours, he said.

Garbarino specifically praised Easterly but criticized the way CISA is enforcing the rules, a common sentiment in the industry. Ultimately, he said, the goal of the Incident Reporting Act was to make reporting to CISA the primary rule, not just one among many. “There are too many regulations in place, and they’re not harmonized,” he said.

Corker said he is grateful for the Senate bill that would establish a council on harmonization that his office will lead, because harmonization is another challenge he wants to address. Easterly praised CISA for going to the effort of seeking feedback from industry on the incident reporting law, even extending the comment period. Both men said they have communicated extensively with industry about their work.

Neuberger agreed, adding that outreach efforts need to balance threats and costs and aim to set “aggressive but achievable” standards for each sector.

On the other hand, as the EPA rule was shelved after the lawsuit, opponents may have made the administration overly timid.

“This was a light touch,” Alan Liska, a senior intelligence analyst at Recorded Future, said of the EPA rule. “This was about basic sanitation; they weren’t asking for anything overly complicated, and yet they were quickly sued.” Other agencies may not take more stringent action, he said, despite differences in who reported the incidents to the SEC.

The administration’s ability to regulate industry has been further complicated by the Supreme Court’s overturning of the “Chevron doctrine,” which states that courts must defer to the executive branch in interpreting federal laws that Congress has not written.

“We’re still analyzing it and figuring out our approach,” Neuberger said.

Suzanne Spaulding, a former top cyber official who ran what was then CISA, credited the administration with making big shifts, particularly reorganizing federal agencies to deal with cyber, but another “really important shift the administration has made is really looking at where markets are taking us and how we can do better,” said Spaulding, now a senior adviser for homeland security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ International Security Program.

Spaulding highlighted the administration’s progress in promoting safe designs and enforcing incident reporting laws.

But overall, she noted, the administration is “trying to make markets more efficient, because we know that’s the best way to do these things. And recognizing the limitations of markets and being courageous and stepping in and regulating where necessary.”

Author: Tim Starks Tim Starks is a senior reporter at CyberScoop. He previously worked at The Washington Post, POLITICO and Congressional Quarterly. A native of Evansville, Indiana, he has been covering cybersecurity since 2003. Email Tim at tim.starks@cyberscoop.com.

Source link