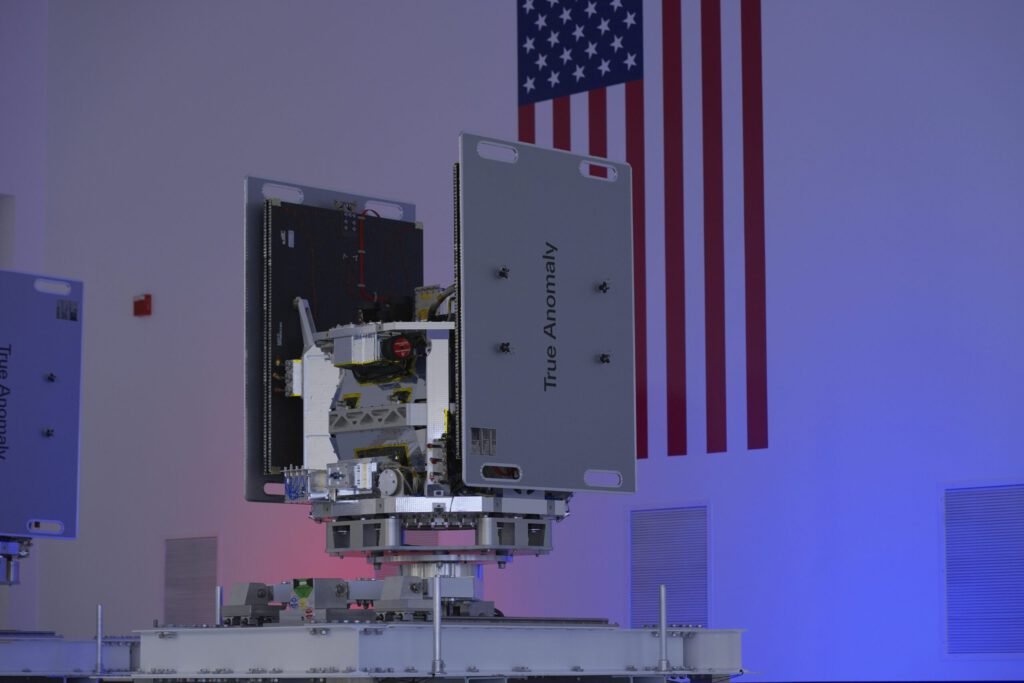

WASHINGTON — Space startup True Anomaly is preparing to launch its first two satellites designed to navigate near, study and photograph other objects.

Founded in 2022 and just closed a $100 million funding round, True Anomaly plans to demonstrate the ability of its Jackal spacecraft to perform orbital activities known as rendezvous and proximity operations.

“The Jackals will capture high-resolution images and full-motion video of each other as they approach each other,” Even Rogers, founder and CEO of True Anomaly, said in a recent interview.

Two Jackal spacecraft, each weighing around 300 kilograms, are scheduled to be launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on the upcoming Transporter 10 ride-along.

The Centennial, Colorado-based company is focused on the military market, aiming to deploy its Jackal satellites to support the operations of the U.S. Space Force, which could use the satellites to train pilots in maneuver tactics, practice close-quarters operations and test payloads in orbit, for example.

“Made for national security missions”

Rogers described Jackal as “a new class of spacecraft purpose-built for national security space missions.” With Jackal, the company aims to compete in an emerging industry segment: extraterrestrial imagery, or imaging of space objects. These capabilities are now available commercially thanks to changes to the licensing process announced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration last year.

True Anomaly received a NOAA license in August for its first Jackal mission in low Earth orbit.

The company aims to deploy additional satellites with similar capabilities and will apply for an amendment to its license: “We will submit new license applications to cover larger constellations, different missions or orbits, including geostationary orbit, and new design variations, as appropriate,” a True Anomaly spokesperson told SpaceNews.

True Anomaly has attracted investors in part because of the hope that it can meet a growing demand for timely, high-quality data about the space environment, Rogers said.

“One of the most significant gaps in space domain awareness is the ability to collect high-resolution, multi-phenomenon data of objects in space,” he said, noting that existing ground-based sensors used to monitor space “don’t provide much intelligence-quality information.”

Military and intelligence agencies trying to identify orbital threats need more detailed data on spacecraft and debris, he said, and “non-Earth imagery is a critical tool to fill those intelligence gaps.”

Each Jackal is equipped with five sensors including radar, shortwave infrared, longwave infrared, visible wide-angle field of view and three imaging payloads: visible narrow-angle field of view.

Non-Earth imagery is a “big market”

Their first mission will see one Jackal take detailed images of the other, demonstrating extraterrestrial imaging capabilities. Two identical craft will fly into orbit, one acting as the “imaging instrument” and the other as the “resident space object.”

Rogers said he was optimistic about non-Earth imaging efforts. The Space Force has not disclosed spending plans for the area, but service leaders said they expect demand for “space domain awareness” to grow as space becomes more crowded and rival nations deploy systems to track and potentially target U.S. satellites.

“Is it a big market? Yes,” Rogers said. “Our previous funding was premised on that fact. We believe extraterrestrial photography is a very important and very large market, and this is based on demand from not only the U.S. government but also from private operators.”

Players in this market include well-established Earth observation companies that already operate satellites equipped with high-resolution cameras and sensors, as well as commercial start-ups specializing in non-Earth imaging.

Rogers said True Anomaly stands out because it offers “close-range, sustained imaging of space objects in a variety of phenomena.”

Once Jackal’s technology is proven in orbit, he said, the goal is to build a constellation of several dozen satellites to monitor the geostationary orbit band 22,000 miles above Earth, where the military’s most important satellites are located.