In 2015, the Australian government introduced an automated debt collection program to curb alleged overpayments of welfare benefits. The program used an algorithm that compared annual salary information from the Inland Revenue Department with income data reported to Centrelink, the national social welfare platform. Six years later, the system had falsely flagged more than 381,000 people and the government was at the center of a class-action lawsuit. In the case, a judge ruled the program was a “shameful chapter” in Australia’s history and had caused “financial hardship, anxiety and distress.”

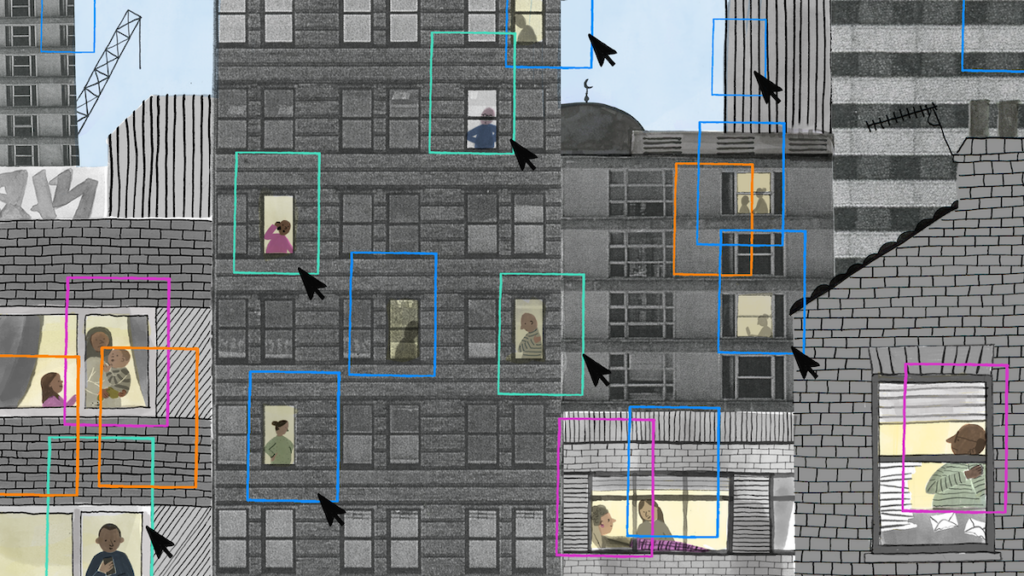

Australia’s failed experiment with a so-called robo-debt scheme is just one example of how governments are increasingly relying on and trusting automated decision-making (ADM) to deliver vital social services. The challenges of automated decision-making in wealthy countries like Australia and the Netherlands are well-documented and well-known among digital rights watchers. But less public attention has been given to the global proliferation of these systems, often with the backing of Western corporations and big donors, in environments where democratic guardrails may be nonexistent or strained.

From Jordan to Serbia, governments are deploying digital tools to automate critical tasks in the name of increasing efficiency and accuracy. The widespread use of artificial intelligence (AI) is accelerating this trend by enabling governments to quickly and cheaply process and analyze the data needed for ADM systems. Integrating automated decision-making into social assistance programs can help under-resourced caseworkers and increase access to benefits.

However, programs that implement ADMs also create a misleading illusion of objectivity and are riddled with inaccuracies, posing a variety of risks, including amplifying existing social biases, jeopardizing privacy protections, and limiting the provision of social services. As ADMs become increasingly common, it is more important than ever to establish principles of transparency and accountability for the digital tools that control access to government services.

Defining Automated Decision-Making: Risks and Benefits

Definitions of automated decision-making vary. Essentially, the term refers to tasks performed by machines or technologies designed to augment or replace human decision-making. On the surface, ADM can make governments more efficient, for example by automating routine tasks. But in reality, ADM systems have a track record of exacerbating discrimination against marginalized groups and undermining important democratic and human rights protections by relying on data that reflects existing real-world inequalities.

In one example, a controversial unemployment assistance program in Poland classified single mothers as the least “employable,” jeopardizing their eligibility for assistance. In 2018, Poland’s Constitutional Court ruled that the program violated the country’s constitution, and the government announced its intention to scrap the program.

Discriminatory decisions often result from inaccurate training data that lacks important historical and cultural context. Take for example the World Bank’s Takaful program in Jordan. The initiative used ADM to distribute poverty relief cash transfers to those who need them most, but ended up disqualifying potential recipients based on inaccurate indicators of poverty, such as electricity usage. The algorithm did not take into account the fact that poor households may consume more energy because they lack access to newer, more energy-efficient appliances.

ADM’s discrimination risk is especially pronounced when used in predictive functions, as biased algorithms can reach inaccurate, misleading and discriminatory conclusions about vulnerable populations. In 2018, the Argentine province of Salta partnered with Microsoft to develop an algorithm to identify girls “destined” for teenage pregnancy and then engage with the selected girls, but it is unclear what follow-up was done. The algorithm made predictions based on several factors, including ethnicity, country of origin and access to hot water, but did not take into account the regional and historical context that shaped the system’s output. Ultimately, the program profiled mostly poor and minority girls and ignored important factors that influence teen pregnancy rates, such as access to sex education and contraception.

Many automated decision-making programs also force potential recipients to surrender their right to privacy, protected by Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). This violation of digital privacy exacerbates socio-economic stratification, creating a system in which only the wealthy have this fundamental democratic right. ADM systems, often with little oversight, collect myriad personal information to create “detailed profiles” of individuals to determine eligibility for welfare benefits. In one example, the South African Social Security Agency partnered with a private company, Cash Paymaster Services, to provide social services. The company required potential recipients to register with biometric information, raising concerns about the processing of personal data and ultimately leading the South African government to abandon the contract.

As welfare systems become more automated and digitalized, digital IDs are often required to access benefits, raising concerns that service delivery is being used as a lever for greater state surveillance. Kenya’s digital ID system requires individuals to provide extensive biometric information, including fingerprints, handprints, earlobes, retina and iris patterns, voiceprints, and digital DNA, and those who do not register risk losing access to social welfare services. In Venezuela, individuals cannot access state benefits without a Homeland ID, created by ZTE, which the government uses to track voting history and social media activity.

Moreover, while governments and international organizations such as the World Bank promote ADMs as a way to improve service delivery to those who need it most, the way these systems are designed could actually reduce access to benefits.

ADM systems developed for social assistance programs are often designed to detect fraud. In reality, welfare fraud is often exaggerated, and programs regularly falsely flag potential recipients, disqualifying them from receiving assistance, usually with little or no remedy or remedy. For example, a Dutch tax authority algorithm introduced in 2012 falsely accused more than 20,000 families of child care benefit fraud. In a scathing report on the spread of digital welfare, a former UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights wrote that automation of social service delivery could limit social assistance funding and lead to a “digital dystopia.” When governments introduce ADM into social service delivery, it could result in the exclusion of certain recipient groups and the elimination of services to vulnerable populations.

A lack of transparency in the design of ADM tools can also allow governments to avoid accountability for systems that could lead to discrimination and exclusivity. ADM programs are often developed in partnership with the private sector, which argues that sharing information about ADM systems raises intellectual property rights concerns. This is the case in Serbia, where the country’s Ministry of Labor has repeatedly denied freedom of information requests from civil society organizations. Regarding the protections given to private sector organizations, technology researcher Shehla Rashid writes: “It is the people who should have the right to privacy and data sovereignty, but it is the mechanisms and practices of algorithms and data processing that are kept secret.” This opacity prevents civil society organizations from exposing and holding governments accountable for the functioning of these systems, effectively allowing technology companies partnering with civil society organizations to operate in a “human rights free zone.”

As digital systems for delivering social services proliferate, the design and use of automated decision-making systems should be guided by fundamental democratic and human rights principles, including transparency, accountability, and privacy. Civil society organizations can push for transparency, for example by filing Freedom of Information requests to learn more about the technology and its sources. Using existing transparency tools can provide a powerful counterweight to government obfuscation and shed light on the role ADMs play in restricting access to benefits.

Digital rights organizations can also contribute to designing independent and impartial Algorithmic Impact Assessments (AIAs) to determine the risks of integrating ADMs into the delivery of social services. As Krzysztof Izdebski explains in a 2023 International Forum for Democratic Studies publication, AIAs can help expose poorly planned digitalization projects. This is especially important in battleground states and fragile democracies, where such tools “may further undermine political accountability that is already under threat.” Actively mitigating the potential harms of ADMs for vulnerable and marginalized groups is a critical step to ensure that automation serves citizens and builds public trust in state institutions.

Moreover, to demand transparency and accountability from their governments, citizens need to be aware of the risks of ADM tools. Civil society can launch education campaigns to inform citizens of the benefits and risks of automated decision-making, providing them with the tools they need to defend systems that are designed with human rights principles such as non-discrimination in mind.

Despite the significant risks posed by ADM systems, automating government processes has the potential to expand the delivery of essential national services. With the right safeguards, digitalization can fit into a positive vision of technology-enabled democracy and can even be an asset to democratic governments and their people. But such a reality can only emerge from a firm commitment to uphold fundamental human rights principles and democratic norms.