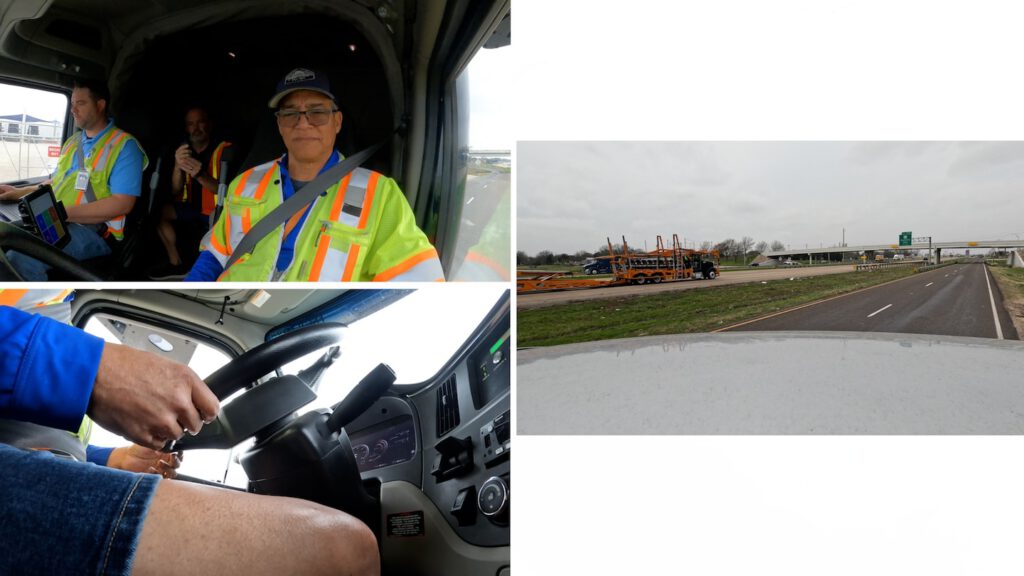

PALMER, Texas — Sitting at the wheel of a 35,000-pound tractor-trailer moving slowly south on Interstate 45, AJ Jenkins watched the road as the steering wheel of the tractor-trailer slipped out of his hands. Jenkins was in the driver’s seat, but he wasn’t driving; the massive 18-wheeler was moving forward on its own.

After traveling several miles on a popular trucking route between Dallas and Houston, the truck dodged tire debris, dodged a battered flatbed and slowed down for emergency vehicles. It exited the highway and a pickup made a sharp turn at a four-way intersection, bringing the truck to a screeching halt.

“You have to be prepared for anything,” said Jenkins, 64, a former FedEx driver whose job it is to deal with problems when they arise. “People do weird things around the truck.”

The truck, operated by Aurora Innovation, is part of a new class of self-driving heavy trucks on the nation’s highways. By the end of the year, two major companies, Aurora and Kodiak Robotics, will launch fully self-driving trucks in Texas, which will make their first forays on the roads without a human driver like Jenkins.

(Video: Rich Matthews/The Washington Post)

The advent of robotic trucks could have a profound impact on America’s supply chains, drastically reducing the time it takes to transport goods from one place to another and freeing the trucking industry from the costs and physical constraints of human labor. But the advancement of this technology has raised concerns about highway safety, job losses, a lack of federal regulation, and variance in state laws regarding how and where autonomous trucks can operate.

Self-driving cars and trucks can travel anywhere in the U.S. unless a state explicitly bans them, meaning companies can test and operate vehicles in most parts of the country. According to data compiled by Aurora, 24 states, including Texas, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada, explicitly allow self-driving cars, while 16 other states have no regulations regarding self-driving cars. The remaining 10 states, including California, Massachusetts, and New York, have restrictions on self-driving cars within their borders.

Alarmed by the delay in federal regulation, workplace safety advocates have pushed bills in several states to ban driverless trucks altogether. So far, the efforts have been unsuccessful. California lawmakers approved a bill last year that would require all self-driving trucks to have human drivers, but Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) vetoed it, calling it “unnecessary” in light of state regulations that already ban self-driving cars weighing more than 10,000 pounds.

Transportation experts have expressed frustration with the slow federal response, given the problem’s potential to disrupt large swaths of the U.S. economy.

Steve Viscieri, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania who studies the trucking industry, said self-driving trucks “have the potential to change the geography of our economy, just as railroads and shipping have.”

“Drivers are seriously concerned about the impacts of this,” Vischeri said. “We need to take that seriously.”

Self-driving cars have caused chaos in cities like San Francisco, including a horrific crash last year when a robotaxi ran a red light and dragged a pedestrian for about 20 feet, and critics say big, self-driving trucks increase the potential for disaster even more.

“Even these small vehicles are a disaster,” said Peter Finn, vice president of the truckers’ union, Teamsters Local 856. “When you think about a big truck going at high speeds down the highway with no humans in it, it’s really scary.”

Massive expansion

Aurora’s long-haul trucks currently transport about 100 packages and produce per week for FedEx, Uber Freight, etc. The company was founded in 2017 by former executives from Uber, Google’s self-driving project, and Tesla, and has been training driverless trucks in Texas since 2020.

Aurora says it plans to have about 20 fully autonomous trucks operating on a 240-mile stretch between Dallas and Houston by the end of the year, with plans to eventually have thousands of trucks operating across the US.

Kodiak Robotics, founded by former Uber and Alphabet Inc. Waymo employees, also plans to launch a fleet of trucks in Texas by the end of the year. A third company, Daimler Trucks, a subsidiary of Germany’s Daimler AG that is partnering with Torque Robotics, is several years behind schedule in planning to launch a fleet of driverless vehicles in the US by 2027.

Aurora’s chief safety officer, Nat Bews, said the self-driving truck industry is “deliberate” in adopting the technology and has adopted rigorous safety standards, including how trucks respond to various system failures. Bews said the company has learned from the mistakes of other self-driving-vehicle makers, such as General Motors Co.’s Cruise, which recalled its entire fleet of driverless trucks after the San Francisco crash.

“The federal government has made it very clear that we can deploy them unless states prohibit us from doing so, but that doesn’t mean that we’re not responsible as a company,” Bewes said. “This is not a science experiment.”

(Video: Jan Elker/The Washington Post)

Texas Department of Transportation Commissioner Mark Williams said Texas has good relationships with the companies testing on the state’s roads and that the state has been “at the forefront” of supporting the industry, which he said is critical to the state’s economic growth as demand for freight increases in the state.

“To address this challenge, we need successful partnerships and collaborations with the trucking industry and the autonomous trucking industry,” Williams said during a February panel discussion with Autonomous Vehicle Education Partners, a coalition of industry advocates.

The average driver would have a hard time spotting one of Aurora’s trucks, as it only has a small sign on the back that reads “Autonomous Test Vehicle.”

But the view from inside a car looks quite different. On a recent February day, two computer screens flashed a series of hazards: tire debris littering the roadside, SUVs and sedans rushing to pass, an SUV merging without using a turn signal.

Vehicle operations specialist Steven Thune sat in the passenger seat, monitoring the screen. He gave Jenkins a running update on the truck’s movements. “I’m pulling right to avoid the tire debris,” Thune said as the turn signals started flashing. “I’m pulling left as a courtesy to the car behind me.”

During the drive, the truck obeyed all road laws and showed exceptional courtesy to other drivers. But unexpected occurrences, from human driver error to sudden mechanical problems, worry veteran truck drivers like Lowee Phyu.

“I know my computer makes mistakes, my phone makes mistakes, and machines have days when they just don’t work,” said Pugh, vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, a national organization that represents professional truck drivers.

Self-driving truck testing has been centered in Texas, but companies also have vehicles on the roads in Oklahoma, New Mexico and other states. Trucks operated by the three major companies have been involved in several traffic accidents since 2021, according to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

None of the accidents resulted in fatalities or serious injuries, but the accident records show the various obstacles the trucks faced.

In July 2022, a Daimler truck ran over an object on a highway in New Mexico, puncturing the fuel tank and spilling oil onto the highway. In December 2023, a deer wandered into the path of a Daimler truck being tested in Texas. The test driver took over driving, but the truck still struck the deer.

Earlier that month, a pickup truck hydroplaned while passing an Aurora vehicle and struck the vehicle’s trailer. Aurora detected the pickup but was unable to avoid the collision.

The two companies will seek success in industries that have faced setbacks: Alphabet Inc.’s self-driving company Waymo said in July it was postponing its trucking business timeline and instead focusing on ride-hailing. Chinese self-driving truck company Tusimple Holdings Ltd. ended its U.S. operations in 2023, a year after one of its self-driving trucks crashed during a test.

Still, self-driving trucks would make highways safer, say those working on the technology: The most recent federal data shows that 5,788 people died in crashes involving large trucks in 2021, accounting for 13% of all traffic fatalities that year.

Technology moves faster than regulations

As profit-driven companies race to adopt them, the federal government has been slow to address the impact of new technologies. The Department of Transportation largely allows companies to test products on public roads as long as they adhere to the same safety standards that apply to traditional human-driven trucks.

Within the Department of Transportation, NHTSA and the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration have been working for more than five years on a proposal to create basic “safety guardrails” for self-driving trucks, including requirements for remote assistants to monitor driverless vehicles, inspections, and vehicle maintenance. The proposal, submitted to the White House Office of Management and Budget in December, would be the Biden administration’s most significant action on self-driving trucks.

Transportation Department spokesman Sean Manning couldn’t say when the rule would be finalized because it still needs to go through some bureaucratic hoops. Until then, existing law prohibits any vehicle, including those with self-driving technology, from “posing an unreasonable risk to safety,” Manning said. Meanwhile, NHTSA will “continue to use its deficiency and oversight authorities to pursue vigorous enforcement, including investigations and recalls when evidence of risk is found,” Manning said.

Both Aurora and Kodiak support the idea of federal regulation, which would give them greater certainty about standards as they expand nationwide.

“Having a federal framework gives regulators and the public confidence that the federal government is closely monitoring this,” said Daniel Goff, Kodiak’s policy director.

Anxious truck driver

Richard Gaskill, a Texas truck driver since 1998, said he sometimes sees self-driving test vehicles while hauling loads on Interstate 45.

“It’s still new and I don’t trust it,” Gaskill, 50, said of the technology. “I hate to think that these things are going to take away our jobs.”

(Video: Jan Elker/The Washington Post)

Gaskill’s fears are shared by labor unions and industry groups like the Teamsters. But a 2021 Department of Transportation study suggests fears of widespread job losses may be misplaced. The study found that autonomous trucks could lead to up to 11,000 layoffs over the next five years, but that represents less than 2% of the long-haul driver workforce.

Meanwhile, the study noted, the technology could create new job opportunities for maintenance technicians, dispatchers and fuelers, while reducing the heavy workload typically associated with long-distance trucking. Autonomous trucking companies also say their technology allows them to move goods around the country faster, because robot trucks can drive for longer periods of time than human drivers.

Gaskill isn’t a believer — he says he can’t imagine a robot could navigate the nation’s chaotic highways better than he can — but he does accept the fact that self-driving trucks are part of the future as companies like Aurora expand.

“It’s just a matter of time,” he said.

Fixes

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the year Richard Gaskill became a truck driver in Texas. The correct year is 1998. The article has been corrected.