Immune rejection remains a major obstacle to long-term survival of lung allografts. Now, a group led by first author Costanca Figueiredo of the Hannover Medical School has significantly improved the survival rate of transplanted porcine lung allografts. Experimental minipigs, physiologically mimicking the human situation, survived for up to 2 years without immunosuppression when swine leukocyte antigen (SLA) expression was permanently downregulated using lentiviral transduction of short hairpin RNA targeting mRNAs encoding β2-microglobulin and class II transactivators. Despite great scientific advances, organ rejection remains a major obstacle. Approximately 25% of kidney transplant recipients lose their organs within 5 years, and lung transplants are rejected even more rapidly due to mismatched molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

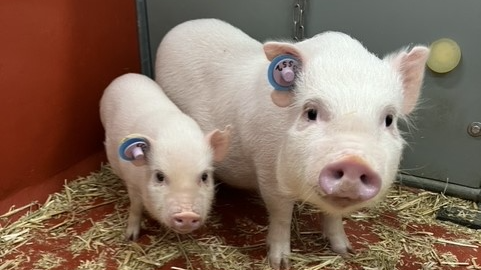

To improve organ survival, Costanca-Figueiredo and her colleagues genetically switched off the expression of swine leukocyte antigens (the human equivalent of MHC) in the pigs’ lungs, in order to avoid unwanted immune responses. In total, seven genetically modified and seven control organs were transplanted.

After four weeks, the team stopped immunosuppression. In the control group, 100% of the organs were rejected within three months. In the Bellum group, five of seven animals retained their lung grafts over the two-year study period and showed reduced SLA antibody and cytokine levels.

“These approaches may be an ideal solution to many post-transplant problems, allowing transplant patients to live free of rejection and immunosuppression, improving graft survival and improving quality of life,” Figueiredo said.