Artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithmic decision-making systems – algorithms that analyze vast amounts of data and predict the future – are increasingly impacting the daily lives of Americans. People are forced to list buzzwords on their resumes to get through AI-driven hiring software. Algorithms are deciding who gets housing and financial loan opportunities. And biased testing software is increasing fears among students of color and those with disabilities that they may be barred from exams or flagged for cheating. But there’s another area of AI and algorithms that should greatly concern us: the use of these systems in health care and treatment.

The use of AI and algorithmic decision-making systems in healthcare is growing, but current regulations may be insufficient to detect harmful racial biases hidden in these tools. Details about the development of these tools are largely unknown to clinicians and the public. This lack of transparency threatens to automate and exacerbate racial discrimination in the healthcare system. Last week, the FDA issued guidance that significantly expands the scope of tools it regulates. The expanded guidance highlights the need to do more to combat bias and promote equity as the number and use of AI and algorithmic tools grow.

In 2019, a shocking study found that a clinical algorithm used by many hospitals to determine which patients needed treatment exhibited racial bias: Black patients were deemed much sicker than white patients before being offered the same treatment. This happened because the algorithm was trained on historical data about medical costs, reflecting a history of Black patients paying less for medical care than white patients due to long-standing disparities in wealth and income. The algorithm’s bias was eventually detected and corrected, but the incident raises questions about how many other clinical and medical tools are similarly discriminatory.

Another algorithm created to determine how many hours of care disabled Arkansas residents should receive each week was criticized for making drastic cuts to home care. Some residents blamed the sudden cuts for extreme disruptions to their lives and even hospitalizations. This resulted in a lawsuit, which determined that several errors in the algorithm, namely errors in how it characterized the medical needs of certain disabled people, were the direct cause of the inappropriate cuts. Despite this outcry, the group that developed the flawed algorithm continues to create tools that are still used in nearly half of U.S. states and in healthcare settings abroad.

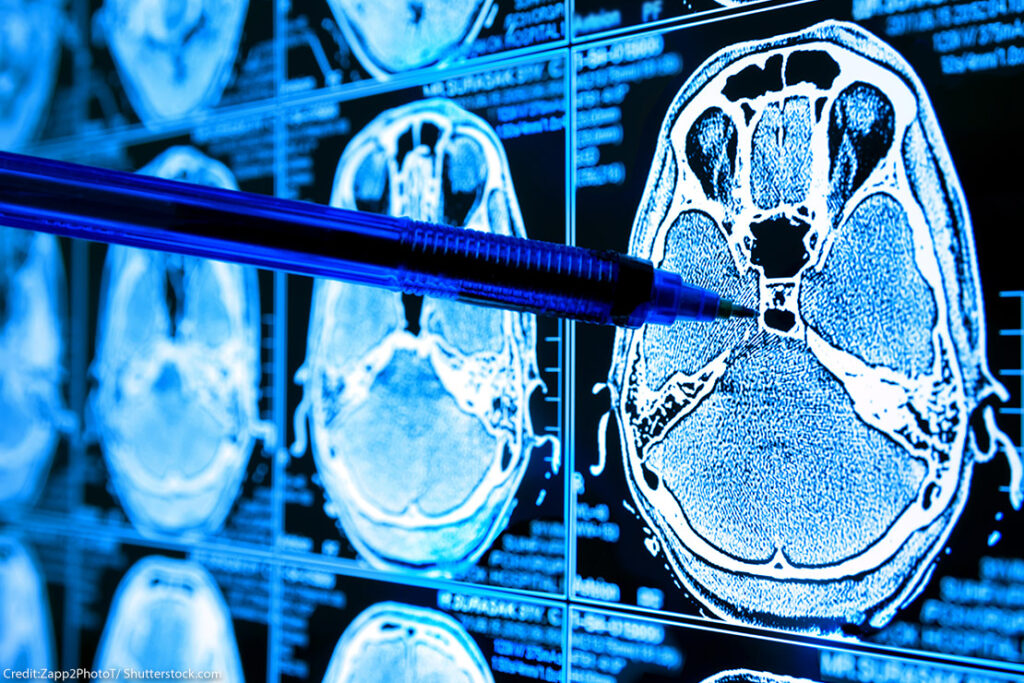

A recent study found that an AI tool trained on medical images such as x-rays and CT scans was able to unexpectedly identify a patient’s self-reported race. The tool learned this despite being trained with the sole purpose of helping clinicians diagnose patient images. This technology’s ability to determine a patient’s race, even when doctors cannot, could be misused in the future, or could unintentionally steer poorer health care to communities of color without detection or intervention.

Some algorithms used in clinical settings are not tightly regulated in the United States. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are responsible for regulating medical devices, from tongue depressors to pacemakers and now medical AI systems. While some of these medical devices (including AI) and tools that help physicians treat and diagnose are regulated, other algorithmic decision-making tools used in clinical, administrative, and public health settings (e.g., predicting risk of mortality, likelihood of hospital readmission, or need for home care) are not subject to review or regulation by regulatory bodies such as the FDA.

This lack of oversight can lead to biased algorithms being widely used in hospitals and state public health systems, increasing discrimination against Black and Brown patients, people with disabilities, and other marginalized communities. In some cases, this regulatory failure can lead to wasted funds and lost lives. One such AI tool, developed to detect sepsis early, is used by more than 170 hospitals and health systems. However, a recent study revealed that the tool failed to predict 67 percent of patients who developed this life-threatening disease, generating false sepsis alerts for thousands of patients who could not have predicted it. Acknowledging that this failure was the result of a regulatory shortfall, the FDA’s new guidelines cite these tools as examples of products that should be regulated as medical devices.

The FDA’s approach to regulating drugs, which involves publicly available data scrutinized by review committees for side effects and events, contrasts with its approach to regulating medical AI and algorithmic tools. Regulating medical AI presents new challenges and requires different considerations than those applied to the hardware devices the FDA is accustomed to regulating. These devices include pulse oximeters, thermal thermometers, and scalp electrodes, each of which have been found to reflect racial or ethnic bias in how they function in subgroups. These news stories of bias only highlight how important it is to properly regulate these tools and ensure they do not perpetuate bias against vulnerable racial and ethnic groups.

The FDA recommends that device manufacturers test devices for racial and ethnic bias before selling them to the public, but this step is not required. More important than post-development evaluation of devices is transparency during development. A STAT+ News investigation found that many AI tools approved or cleared by the FDA do not include information about the diversity of the data on which the AI was trained, and the number of these tools being cleared is growing rapidly. Another study found that AI tools “consistently and selectively underdiagnose underserved patient populations,” with higher rates of underdiagnosis in marginalized communities that lack access to medical care. This is unacceptable when these tools may make life-and-death decisions.

Fair treatment by the healthcare system is a civil rights issue. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the many ways in which existing social inequalities create healthcare inequities. This is a complex reality that humans can attempt to understand but that is difficult to accurately reflect in algorithms. The promise of AI in healthcare was that it could remove bias from biased institutions and improve healthcare outcomes, but in reality, it threatens to automate this bias.

Addressing these gaps and inefficiencies will require policy changes and collaboration among key stakeholders, including state and federal regulators, medical, public health, and clinical advocacy groups and organizations, as detailed in a new ACLU white paper .

Public reporting of demographic information should be required. FDA should require an impact assessment of differences in device performance by racial or ethnic subgroups as part of the clearance or approval process. Device labels should reflect the results of this impact assessment. The FTC should work with HHS and other federal agencies to establish best practices that non-FDA-regulated device manufacturers must follow to mitigate the risk of racial or ethnic bias in their tools.

Rather than learning about racial and ethnic biases embedded in clinical and medical algorithms and devices from shocking publications exposing medical malpractice, HHS, FDA, and other stakeholders must work to ensure that medical racism is a relic of the past rather than a sure thing of the future.