The automated cashier isn’t an AI, it’s someone in India. Amazon made headlines this week for rolling out its “Just Walk Out” checkout system, where customers simply pick up their in-store purchases and walk away while a “generative AI” tallys up the receipt. But as The Information reported, the system wasn’t as automated as it seemed: Amazon simply relied on Indian workers to review in-store security camera footage and create an itemized list of purchases. Instead of saving on cashier costs or training better systems, costs have grown and the promise of a perfect technological solution has become even more distant.

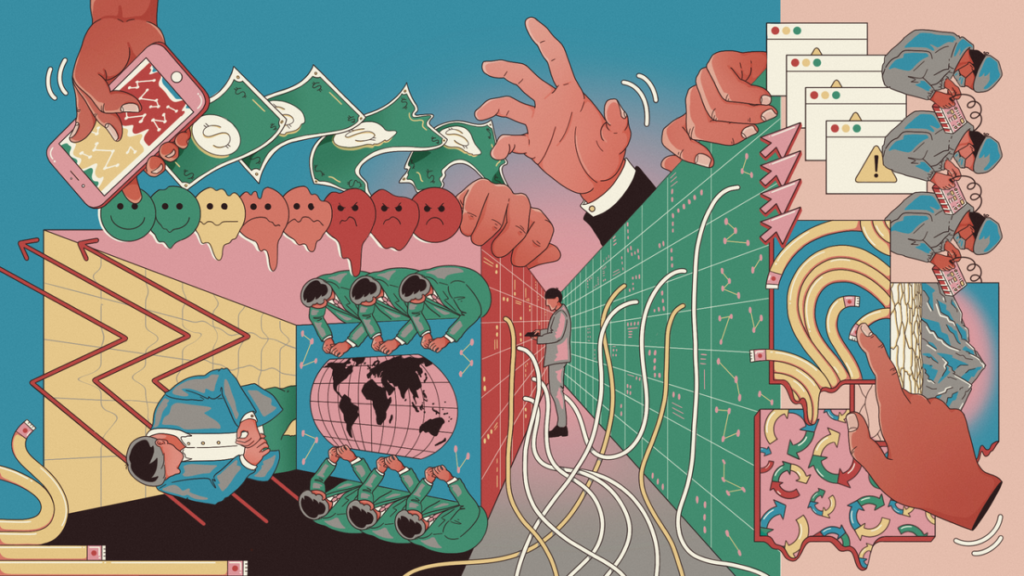

For businesses and investors, the promise of AI is that it will enable companies to increase profits and productivity by dramatically reducing their reliance on skilled human labor. But as this story and many others show, AI is little more than today’s buzzword for “outsourcing,” with the same problems that have plagued the companies and workforces they outsource to for decades.

Amazon’s story is by no means unique. Years ago, Microsoft teammates Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri called it “ghost work” and blamed it on the “last mile” problem of automation, the ever-increasing limits of what computers, not humans, can achieve. According to Sarah Roberts of the University of California, Los Angeles, Meta’s invisible army of content moderators magically erase objectionable content from news feeds, at the expense of our mental health. In his new book, sociologist Benjamin Shestakovsky recounts life at a startup where, while the US-based engineering team was busy interviewing new employees and scaling to please investors, the company offshored its entire AI product to workers in the Philippines, task by task. My Princeton colleagues and I described a process we called “pre-automation,” in which companies hire humans to perform tasks promised by automated systems, squeezing unpaid labor and investment capital on the one hand and deregulating the sector for monopolies on the other.

In these cases and many others, “AI” is a shiny distraction that asks us to “pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.” But behind that curtain lies the familiar phenomenon of outsourcing: the exchange of expensive, skilled labor in the United States and other developed countries for cheap, unskilled labor in the developing world.

Indeed, job losses related to “AI” are reminiscent of those associated with deindustrialization in the late 20th century. These losses accumulated in geographic locations or market sectors as labor shifted overseas to emerging markets and more people were asked to do lower-paid, lower-skilled jobs. As investors sought to squeeze ever more profits, the United States transformed into a “knowledge economy” dominated by managers and hollowed out by technical expertise.

The creative accounting techniques that gave us “fast fashion,” offshore call centers, and the ill-fated Boeing MAX-C are the same ones that led Amazon to install empty cash registers with Indian workers who it hoped could do the same work for less. But studies show that outsourcing increases interorganizational complexity and communication challenges, leading to greater inefficiencies and lower quality for consumers. Meanwhile, studies of automation find that the result is greater labor needs and inequality, with new skilled workers to oversee the machines and workers to take on lower-skilled roles. As anthropologist Lily Irani points out, labor isn’t replaced by machines, it’s simply displaced. While restructuring has caused stock prices to soar, few companies have realized this promise of savings and profitability, and “menial jobs” have proliferated.

Talk of AI distracts us from these familiar, uncomfortable moments. Instead, we imagine a glorious “future of work” in which we’re all miraculously more efficient, our workplaces are filled with relentlessly affable robots, and skilled automated agents carry out our every command. Commentators speak high-mindedly of “AI ethics” as if it were a technical issue, like making AI bias-free or building BB-8 instead of the Terminator.

But the future of work isn’t technology. It’s deployment. The deployment of people, capital, and labor to move jobs from expensive, high-paying places to cheaper, more menial places. “AI” is a powerful decoy, keeping us from starting to think about where those jobs have already gone (overseas) and who moved them there in the first place. Because robots won’t “take our jobs,” humans will.

We need to see beyond the shiny surface of new technology and future-oriented promises in the “AI” pitch. It’s just old wine in new bottles, and as the Amazon story makes clear, it’s already turning to vinegar. U.S. policymakers and workers would be wise to heed the lessons of the past 40 years of outsourcing and its effects on the labor market, and act quickly to legally protect domestic skilled workers and not neglect foreign partners. Customers of companies adopting AI should demand that they keep high-level experts on the front lines of production and not let complex jobs be scaled back or reduced to menial tasks. And the next time a CEO shows us a pitch emblazoned with AI references, investors should follow Amazon’s lead and “walk away.”